It's Time to Acknowledge Men and Women Behave Differently

By Tessa Shaw

We need to accept that men and women behave differently, in part, because of the different expectations society has of them, and find ways that work with these differences rather than against them.

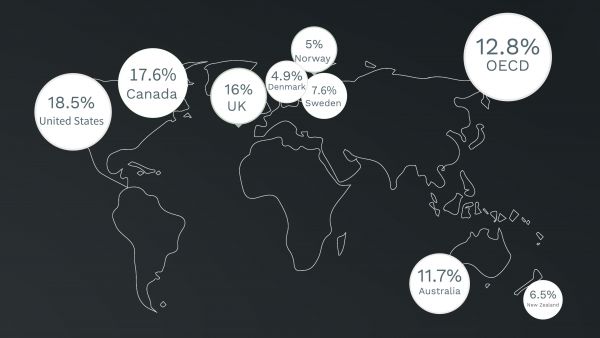

Despite a number of policies that have been introduced to address gender differences in pay gaps, the disparity still persists. As a nation, generally, we are doing better than other OECD nations, but worse than in many others. Our gender gap in pay among full-time employees is larger than that documented in the Scandinavian countries such as Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, as well as France and New Zealand, but smaller than in the UK, Canada, the US, and only a sliver below the aggregate statistic across all OECD nations.

In Australia, women working full-time earn on average between $0.80-$0.88 per $1.00 earned by men.

To address these gaps in pay, researchers have turned to an important determinant of wage differences: the negotiation of pay.

Dr Maria Recalde says that her recent research, a review of the literature on gender differences in negotiation, has revealed that there are gender differences in both willingness and ability to negotiate. “Men are generally more likely to initiate negotiations for higher pay than women,” says Dr Recalde. “There are also significant differences in the outcomes of the negotiations when it is not clear what is negotiable and what the bargaining range is.”

Dr Recalde also adds that research has shown that these differences are larger when the negotiation activates gender stereotypes, or when it violates gender norms, and when individuals negotiate on behalf of themselves rather than on behalf of others.

To combat this, several initiatives have been implemented to reduce differences in negotiation and the effect that such differences have on labour market outcomes. To further study how effective these initiatives are, Dr Recalde and her co-author, Prof Lise Vesterlund (University of Pittsburgh) classify them into two genres: ‘Fix-the-women’ and ‘Fix-the-Institutions’.

“What we call the ‘fix-the-women’ approach seeks to change the way women behave – encouraging women to negotiate more, acquire better negotiation skills, and, as Sheryl Sanberg famously puts it, to ‘lean in’” says Dr Recalde.

However, her overview of existing research reveals that these initiatives do not necessarily work and even have the potential to backfire in part because they fail to recognise that men and women are often treated differently.

According to Dr Recalde, women know when negotiations benefit or disadvantage them, and opt out of negotiations that they deem are costly to them. They also tend to ask for lower pay rates than men, in part because they know that they will experience backlash when asking for higher pay, while men tend not to experience such backlash.

This clearly shows that encouraging women to behave like men is not sufficient in eliminating gender differences and in reducing bias.

By contrast, Dr Recalde and her co-author have concluded that initiatives that aim to ‘fix the institution’ seem promising, and include strategies such as pay transparency and making pay less dependent on negotiations and on past salary histories.

“By implementing policies that seek to make wages at the occupation and position level more transparent, organisations can present all employees with the same information,” says Dr Recalde.

This allows everyone to set similar expectations at the negotiating table, which means that organisations could reduce, and possibly even eliminate, gender differences in negotiation and in outcomes.

“Negotiation bans like the one implemented by Reddit in 2015, have also been shown to reduce differences in pay in a laboratory experiment. Empirical analysis of salary history bans implemented by several US states also show that the policy has reduced the gender pay gap, with no impact on labour-force participation or turnover rates.”

However, Dr Recalde also stresses the importance that initiatives that focus solely on banning negotiations or disclosing of salary histories may not be sustainable in the long-run. If rival organisations use negotiations to attract away talent, a company that has banned salary negotiations will eventually have to use negotiate again. Similarly, if people choose to disclose their salary histories voluntarily at the interview stage when seeking new employment, then the policy will unravel.

Dr Recalde views policies that push for pay transparency as the most promising. “In Canada and Denmark, this transparent model of salary information and pay expectations has already been shown to reduce gender pay gaps,” she says.

But, such policies need to be fully transparent. Once again, this boils down to men and women behaving differently. “Research suggests that partial transparency policies, which allow workers to freely choose whether to discuss salary information, are likely ineffective because men and women have different communication patterns,” she explains. “Women tend to be more private about wages than men.”

There are current policies in place in Australia, such as the Workplace Gender Equality Act 2012, which requires non-public sector employers with 100 or more employees to submit a report to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency.

Among other data, organisations report information on workforce composition, pay, appointments, promotions, resignations, and parental leave. This points to some form of transparency policy already in place in Australia. However, more disaggregated statistics could be provided to provide a clearer picture for workers who may want to use this information at the negotiating table.

“We can certainly do better,” Dr Recalde says. “First, we need to recognise that initiatives that focus exclusively on ‘fixing women’ cannot work.”

She also encourages governments and organisations to implement changes such as advertising pay ranges in job postings, and making it clear if, and which, terms are negotiable. She is confident that given the effort and resources already devoted to reducing gender gaps in the workplace in Australia, embracing policies that ‘fix the institutions’ can go a long way in closing these disparities.

We need to change the environments that give rise to gender differences in the workplace.”